Can you apply service design principles to fix a fragmented NHS?

Big thoughts sparked by Hayley Gullen

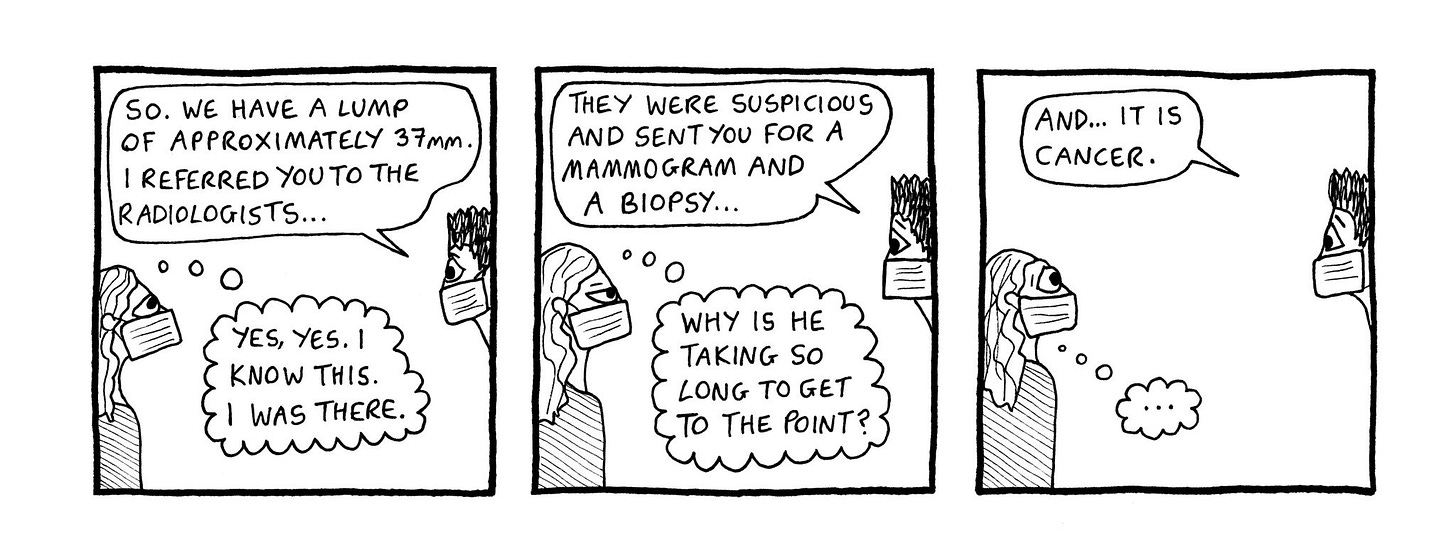

I recently read This Might Surprise You by my friend Hayley Gullen. It’s a graphic novel memoir of her experience of breast cancer treatment. For such a heavy topic, it is incredibly funny and observant of the weirdness of undergoing complex medical treatment within the UK’s National Health Service (NHS).

What I found most surprising was how it made me think a lot about the work we’re doing to build a new national breast screening digital service. It was fascinating to see the descriptions of issues that I encounter in day to day work reflected in a patient’s experience. It also demonstrated the confidence you need in order to advocate for yourself when navigating the organisational complexity of the NHS.

Hayley’s experience also demonstrates the similarities between poor digital user experiences and poor experiences interacting with the healthcare bureaucracy. Some of the issues are a consequence of poorly implemented integrations, but not all of them.

It made me wonder if there should be an analogous service standard for patient care that could be deployed in the NHS. This might help with that fragmentation and the feeling of overwhelm for patients when they are forced to interact with a system, that while ostensibly about healthcare, often emphasises efficiency or cost effectiveness for the organisation over what patients expect from a national health service.

Principles based care

One of the things that Hayley’s experience reminded me of were the early days of GOV.UK when we were rationalising thousands of websites. Obviously the main departmental ones (such as Department of Transport) and Arms Length Bodies (such as DVLA), but then a myriad of sub-sites, campaign sites, service sites, all with different designs and language.1

We realised very early on that those hand offs between one agency and another would be incredibly confusing for users, as each policy team named key terms and described similar processes very differently. The result was that users were left to try and decipher what the policy or service actually wanted them to do or even if they were eligible.

I see this very much reflected in Hayley’s story. She experienced basic technology not working, or had her appointments constantly rescheduled at the last minute, or that key letters weren’t delivered because of old address data. She was left to decipher a complex web of unconnected services and misleading information to receive her treatment. It took Hayley, and no doubt everyone who deals with a long-term health care issue, a phenomenal amount of effort to just get to their treatment.

These unconnected services, relying on the sheer determination of users to complete them, were all very familiar problems from my experience at GDS and my current work in the NHS.

The problem is that even though there are various governance processes to get something bought or built by a NHS Trust, the incentives are not necessarily aligned in a way that prioritises patient experience over other things like how much it costs. I imagine clinical information is included in procurements, but the value of the contract or the true scale of the integration challenge means that critical parts to create an intuitive service get deprioritised. Instead, organisational work arounds are created to ‘join up’ the service - but it never feels coherent for the people navigating the now fragmented journey.

In digital we started to solve this with a principles based approach, defined in the GDS Service Standard. We changed the focus from what it costs and ‘usability testing’ to solving a whole problem for the users of a service, or reducing dependency on legacy technology, or ensuring that services are accessible.

After reading Hayley’s graphic memoir, and seeing the similarities, I wondered if the same principles based approach could apply to healthcare.2 There is the NHS Constitution - but while it talks about best value for money, working across boundaries, patients being at the centre of care, and high standards of professionalism - it clearly doesn’t translate into user focussed services. Perhaps the point on professionalism could extend to organisational professionalism - ensuring that data is joined up or that patients aren’t expected to navigate organisational complexity on their own.

I know digital and healthcare are very different. I’m not saying we need a service standard, but I do wonder if it’s possible to apply principles based approaches to something as risk averse as healthcare. There are real organisational needs like efficiency and cost to consider - but ultimately you are building and commissioning services for people to use them. It’s also incredibly inefficient if letters don’t arrive or the service is so disjointed that patients end up missing or rescheduling appointments as a result.3 It feels that the NHS constitution could be a starting point - but maybe that’s too mired in governance or other processes to be the right place.

There’s one story in Hayley’s book that encapsulates the issue. Basically, she has a small complication - but it’s very obvious and persists for awhile. Eventually, it comes to a head and she advocates for the treatment she wants. There are then some knock on effects and behaviours that leads her to make a complaint. From this complaint, change happens! But why did it have to take a complaint in the first place?

From my work I could just see the list of Standard Operating Procedures or Right Results procedures at play.4 If X happens, then do Y. But what if there’s no further instruction, and staff keep repeating the same process, despite it not improving the situation? What if there was a principle of ‘if something looks wrong, and it doesn’t improve, find a better solution’ or ‘talk to the patient about options'. From an outside perspective, checklists to ensure that certain procedures are done to a certain ‘professional’ standard look completely broken if it doesn’t improve the situation or makes it actively worse.

The complexity of the NHS manifest

The other amazing part of Hayley’s book was how well it managed to convey the bewildering complexity of the NHS.5

From a commissioning perspective, having different hospitals or units deliver different services within a single Trust makes total sense. You want to provide different services at a low cost, because that’s efficient…at least for the commissioning unit.

When you get ping-ponged around different hospitals, units and doctors, it suddenly seems incredibly disjointed and impersonal. This is especially the case when communication is fragmented and people engaged with treatment don’t understand why you have to go to these different places.

There was another bit in Hayley’s book where the hospital has her old address - and I was brought back to Covid days working on the food parcel service. We received address data from healthcare data to send out the parcels - but there’s not just one healthcare record for each person, there are multiple records depending on how many places you’ve been for any kind of treatment.

The one that is most accurate is the one you gave your last address to. So if you had a hospital appointment in 2010, that would be the last address it had, even though you told your GP in 2015 that you moved somewhere else. This is why the idea of a Single Patient Record is so intriguing as it’s a first step to unifying a patient’s data across a fragmented estate.6 In the case of Hayley, she almost missed an appointment because there isn’t a single view of any patient, due to the decentralised nature of technology in the NHS.

I’m not sure how you balance the cost of commissioning the delivery of healthcare with other important needs. It will come down to procurement guidance, finance and strategic interests of each individual Trust. Perhaps, just like it was with digital service delivery, there has to be more emphasis on user needs, continuity of services or patient care that form the basic requirements of the procurement.7 Or understand how the commissioned service joins in with other healthcare streams. With long term treatment, you’re moving around multiple departments, which don’t often look like they talk to each other very well. But how do you commission an end-to-end service when it might be a node in 20 different clinical pathways?

The other complexity is the capability of the different staff involved. It’s easier to apply standards based approaches when you have highly skilled digital staff, who have the luxury of time to investigate, analyse and design better interventions.

Many staff in the NHS are not going to be in the same position - they will not have the time in their day to day work to think about these complex, interrelated issues. Nor will the clinical teams or hospitals have the money to do so. There are no doubt incredible, superhuman staff trying to improve their areas - but they are the exception8. Lots of staff are just trying to deal with the myriad of constraints placed upon them to deliver their service as best as they can without leading to a dreaded ‘incident’.9

There needs to be some slack in the system for continuous improvement - and Hayley’s book once again was so accurate in conveying the lack of capacity and time within the NHS for that to be a possibility.

Fixing the basics

Fixing just digital and technology in the NHS is going to be a multiple decades endeavour. I’d love to be wrong, but we’ve barely scratched the surface of legacy tech in government and we’ve had 13 years of work there.

But at least with the work we’re doing in my tiny corner, we’re looking at the patient experience with an aim to make it better.10 The fragmented experience that Hayley had during her treatment has been reflected many times from the stories we’ve heard from user research and working with clinical staff. It’s hard for the staff to have top-notch patient care when they only see a slice of the patient’s relevant medical history.

Hayley was too young to be on the breast screening programme and so she went for symptomatic screening.11 For any interaction outside the National Breast Screening Programme, that information is now locked in the hospital system where that procedure was carried out. When that person then goes for their first screening (or subsequent screening) appointment as part of the National Breast Screening Programme, that data is stored in a separate national system, which means screening teams won’t know what happened at that previous symptomatic appointment. At the moment, it relies on the patient to relay complex medical information that they assume screening teams have already.12 The expectation from patients is that the screening programme should know about their medical record because it’s a National Health Service, isn’t it?

Hopefully within screening, we’re going to fix some of these problems. Precisely because we are taking that standards based approach - what are the user needs - and trying to solve a whole problem, despite the complexity. If we’re successful, it will improve both experiences of the screening teams and screening participants dramatically.

In the meantime, buy Hayley’s graphic memoir, it’s a delight.

Please observe a minute of silence for the rationalisation of HM Courts and Tribunals websites which took TWO YEARS.

I’m almost sure someone’s probably already thought of this, but I’m not letting reality get in the way of a good post.

Exacerbated by the fact that you are going through the mental and physical effects of an illness that requires long term treatment, with multiple interventions.

These are processes and checklists that should help clinical staff avoid an incident - for example missing someone who is entitled to screening or failing to send their results from the screening episode.

I’ve watched enough American YouTubers to know that this is not just an NHS problem.

This will not be an easy thing to implement.

There were some services built by government that were technically ‘free’ to operate because the supplier charged a fee for the service to the user. So on paper, sweet deal for the government, but in reality they were the most complained about services on GOV.UK because there was no incentive to improve them.

We’ve met a few of them in screening already.

The one that is a major part of Breast Screening is the Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposure) Regulations, if you want a taste of the regulatory environment normal admin staff need to operate in.

And hopefully increase uptake rates if it becomes an easier experience to manage for screening participants.

Symptomatic screening is when you have a symptom, like a lump, and get it checked out, either because you’re too young to have entered the screening programme or its in between your screening schedule (which is every 3 years after you turn 50).

This can be especially infuriating when the hospital and the breast screening unit are in the same NHS Trust. So the expectation from patients is completely reasonable, it’s the technology and lack of data integration that is the unreasonable element in this situation.

I've found your articles on your detailed experience in this area incredibly helpful. It's really useful to have examples like hospital and GP address records being on different systems. Never occurred to me, but yes, I can see exactly how that would have happened, and what a pain it would be to fix such an apparently small thing after the build. Thanks very much.

I think design approaches to integrating services are happening in the NHS - but they are happening at primary care level, in neighbourhoods, in collaboration with local government that provides adult care services, so that the person sees a single service wrapped around them, instead of being bounced between things. These are aimed at more intense users, for both prevention downstream in acute care, and for better outcomes for the person concerned. Some info here - https://www.cnwl.nhs.uk/news/camdens-first-integrated-neighbourhood-team-here

I think one of the issues though is that it actually induced demand - as people now get access in the round rather than in solos that might miss something